Minor Olympian Gods

Minor Greek Deities

Apart from the 12 Gods reigning at Mount Olympus, the ancient Greeks also worshipped other lesser deities, semi-gods or creatures of divine origin. Although their force or influence was not meant to be compared with the Olympians, they were assigned to carry out specific pre-arranged duties.

Each one of the Lesser Deities was responsible to perform a series of diverse tasks. Some became simple messengers of the Olympian will towards the mortals (such as Iris), while others played the role of the protector of certain values, ideas or qualities. Thus Asclepius, Hebe and Eileithyia were gods related to health (healing, youth and good labor respectively) and the Muses, Graces, Fates, Themis and the Hours affected everyday life (creativity, beauty, destiny, justice and social welfare.

The ancient Greeks also believed in certain divine entities inhabiting the springs, river sources, and mountains such as the attractive Nymphs, in creatures wandering in the forests and cliffs such as Pan and his Escorts (Satyrs and Maenads) and in flying monsters traversing the skies like the terrifying Harpies. Dionysus, the god of joy is examined separately in the Dionysian cult section.

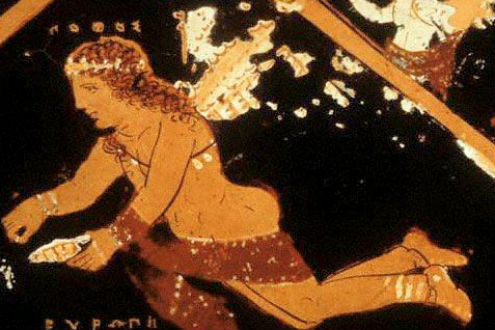

Similarly, the seas were not left unoccupied by such beings. There dwelled the Nereids, Sirens, Triton, Proteus and the terror of sailors, Scylla & Charybdis. Last but not least, the heavens wept the tragic doom of Helios’ son, Phaethon.

“Upon my word, just see how mortal men always put the blame on us gods! We are the source of evil, so they say - when they have only their own madness to think if their miseries are worse than they ought to be.”

Homer, The Odyssey Tweet

Gods and Goddesses

- OLYMPIAN GODS

- TITANS

- UNDERWORLD GODS

- PRIMORDIAL GODS

- SEA GODS

- SKY GODS

- RUSTIC GODS

- AGRARIAN GODS

- DAEMONES

- DEIFIED MORTALS

OLYMPIAN GODS

- Aphrodite

- Apollo

- Ares

- Artemis

- Athena

- Demeter

- Dionysus

- Hephaestus

- Hera

- Hermes

- Poseidon

- Zeus

TITANS

- Cronus

- Oceanus

- Iapetus

- Hyperion

- Crius

- Coeus

- Rhea

- Tethys

- Theia

- Phoebe

- Themis

- Mnemosyne

MINOR TITANS

- Helius

- Selene

- Eos

- Leto

- Asteria

- Hecate

- Pallas

- Astraeus

- Perses

DAEMONES

- Dike

- Eris

- Eros

- Geras

- Hebe

- Hygeia

- Hypnos

- Lyssa

- Mnemosyne

- Nemesis

- Nike

- Peitho

- Phobos

- Plutus

- Poena

- Pothos

- Soteria

- Thanatus

NYMPHS

- Nymphai

- Aurae

- Dryades

- Hesperides

- Naiads

- Nereids

- Satyrs

- Tritons

HEROES and VILLIANS

- Bellerophontes

- Ganymede

- Heracles

- Pandora

- Pasiphae

- Perseus

- Phaethon

- Psyche

- Triptolemos

BESTIARY

1. SUB-BESTIARIES

- Dragons

- Giants

- Legendary Creatures

- Legendary Tribes

2.MONSTERS & CREATURES

- Centaurs

- Cerberus

- Cetea

- Chimera

- Giants

- Griffin

- Harpies

- Hippocamps

- Lernaean Hydra

- Gorgons & Medusa

- Minotaur

- Pegasus

- Satyrs

- Skylla

- Sirens

- Sphinx

- Tritons

- Typhoeus

- Labors of Heracles

GIANTS

- Alcyoneus

- Aloadae

- Antaeus

- Argus Panoptes

- Cyclopes

- Cyclopes

- Enceladus

- Geryon

- Gigantes

- Polybotes

- Polyphemus

- Porphyrion

- Talos

- Tityus

- Typhoeus

LEGENDARY CREATURES

- Amphisbaena

- Basilisk

- Catoblepas

- Griffin

- Harpies

- Leucrocotta

- Manticore

- Unicorn Horse

- Onocentaur

- Phoenix

- Sirens

- Yale

- Ethiopian Bull

- Indian Cetea

- Indian Dragon

- Ethiopian Pegasus

- Satyrides Satyr

- Tanagran Triton

LEGENDARY TRIBES

- Libyan Satyr & Aegipan

- Arimaspians

- Blemmyae

- Centaurs

- Cynocephali

- Gegenees

- Gorgades

- Hippopodes

- Machlyes

- Nuli

- Panotii

- Pygmies

- Sciapods

Grace, Beauty

Charites - Gratiae

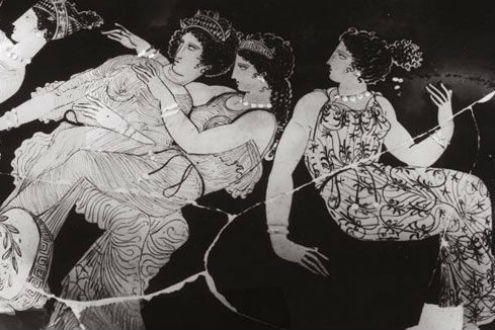

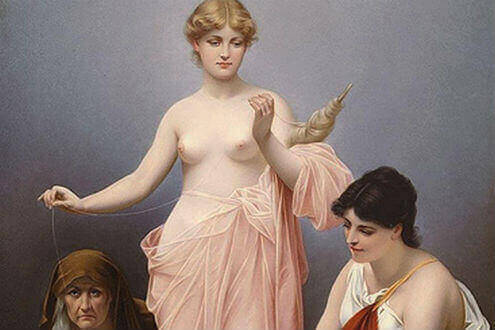

The Charites (Χάριτες) are in Greek mythology goddesses of grace, who communicate with Aphrodite and correspond in Roman mythology to the three Graces, gratiae.

They are daughters of Zeus and Eurynome and are called Euphrosyne (the “happy ones”), Thalia, also Thaleia (the “Flowering”) and Aglaia (“Radiant”). The three graces were a popular subject of fine art and were mostly unclothed, touching or hugging each other. One of the most famous paintings – “The Three Graces” – is by Raphael currently housed in France at the Musée Condé in Chantilly.

The name

The name is derived, according to Phurnutus (aka Cornutus: De natura deorum), from gr. Chara “the joy”> gr. Charis> lat. Gratiae.

Special names and their number

Some ancient sources, according to Pausanias of Cesarea of Cappadocia (Greek historian of the 2nd century) call only two graces:

As they worshiped the Athenians since ancient times:

Auxo (not to be confused with one of the hearers, daughter of Zeus and Themis)

Hegemone

How they worshiped the Lakedemonians in Laconia:

Phaenna (“the Shining, Shining”)

Kelita

Most ancient sources, like Hesiod, name three graces:

Aglaia (as Charis’s wife of Hephaestus (Vulcanus));

Thalia (not to be confused with the muse for the comedy, daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne);

Euphrosyne, also called Euphrone according to Phurnutus.

The youngest [which?] Is sometimes called Pasithea, according to Homer’s Iliad.

A grace called Pitho or Suadela, according to Pausanias in some sources added as the fourth or is called according to Aristophanes instead of Euphrosyne.

Homer first mentions a Grace, who was the wife of Hephaestus. He also tells the story of one of the Graces who was married to Hypnos (=Sleep): Hera had promised her to this god, in exchange for his service in putting Zeus to sleep so that the gods could involve themselves in the Trojan War. At a later period, the Graces were generally considered to be three inseparable sisters, daughters of Zeus and Eurynome, named Aglaia (Brightness), Euphrosyne (Joyfulness) and Thalia (Bloom). They inhabited the summit of Mount Olympus, from where they arranged all things, ceaselessly singing hymns of praise to their father, the king of the gods. They spent much of their life feasting, as their presence was essential at the banquets of the gods: without the Graces, there could be neither pleasure nor dancing. They usually sat next to Apollo, praising Zeus and adorning the assemblies with their presence and their melodious voices.

They were also, with Hebe, Ganymede, the Hores, Harmony and Aphrodite, the dancers of the Olympian company. Besides, they were extremely fond of music, singing, poetry, dancing and rhetoric, and are very often found in company with the Muses. It was the Graces who bestowed on mortals all the wealth and the virtues they possessed: beauty, wisdom, glory – even entertainment, pleasure, joy and happiness were their doing. But above all they were the goddesses of physical grace and of the beauty which enchants. It was they who bestowed upon mortals the allurements that encourage love and pleasure, in the noblest and most seemly dimension of these terms. In this way, human life acquires substance and significance. Moreover, the Graces themselves had many gifts, and were able to excite desire: their hair, face and hands shone with an effulgent beauty, and their deportment was everything that is graceful. The Graces may be likened to a “Triple Aphrodite”, for their Venus-like character is both evident and effusive. Aphrodite, for her part, is the divinity with whom mythology mainly associates them, as she was the goddess of love and beauty; together with Eros and Peitho, the Graces were her most constant companions.

Once Aphrodite had an unpleasant adventure: she had been caught in the net of Hephaestus, together with her lover, Ares; afterwards, she sought refuge in Paphos, on the island of Cyprus, where the Graces assumed her care – bathing her, anointing her body with everlasting oil, rubbing her in wonderful garments and adorning her. In the same manner and with equal care they set off her celestial beauty, when she was preparing to seduce the Trojan Anchises. This ‘aphrodisiac’ character is also seen in their mastery of the art of preparing perfumed oils to make the skin smell sweet, thus reinforcing erotic desire. They were in fact renowned for their skill as perfumers.

The Graces had good relationships with many other gods, and no dispute could ever affect them. They often accompanied Zeus and Hera, together with Dionysus, Demeter, Hermes, Hephaestus and Athena. When the infant Apollo began to play his lyre, the Graces and the other goddesses at once began to dance. And when Artemis entered her brother’s temple at Delphi, the Graces joined with the Muses in singing the praises of their mother. Without these divinities, Mount Olympus would have been entirely lacking in grace. Indeed, at the divine banquets the first cup was dedicated to the Graces, to Dionysus and to the Hores.

There were several places of worship dedicated to the Graces, throughout the length and breadth of Greece: in Athens, indeed, they had a temple on the Acropolis and statues in the heart of the city. The most ancient sanctuary of the Graces was located in Orchomenus in Boeotia, where as legend has it, three rough stones were dropped from heaven. These stones were regarded as representing the three Graces, and people made their offerings there, later dedicating statues to the goddesses. The cult of these “heaven-sent stones” shows that the concept of their celestial origin was general. Indeed, many held that their father was Uranus; this is reinforced by the fact that in many places their names and worship have been associated with, the goddess of the Moon. In Boeotia, special festivities, called “Charitiae”, were held in honor of the Graces; these included both music and poetry. At night, the assembled multitude would dance and offer up cakes made of flour and honey. These festivities were very similar to real “mysteries”, with the Graces venerated as natural deities, offering fertility to the plant kingdom.

Relieve

Eileithyia - Lucina

The goddess Eileithyia belongs to the main gods of Greek mythology, but not to the Olympic gods in the strict sense, since she did not reside on the Olympus.

She is the goddess of birth and protector of childbearing women. She is also a daughter of Zeus and Hera. The birthplace of Eileithyia was on Crete in the Cave of Amnissos.

Because she brought children into the light, she was usually presented with raised hands. However, a representation as a torch-wielding woman is also widespread, which should symbolize the burning pains of birth and reproduce them metaphorically.

Eileithyia in the myth

The goddess can influence a birth in two ways: either she promotes the process or prevents the onset of labor, whereby the woman is no longer able to give birth to a child and suffers great pain.

God of love

Eros - Ἔρως - Amor

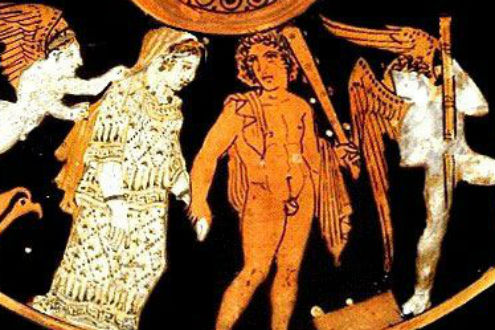

Eros (Greek Ἔρως) in Greek mythology refers to a god or demon of covetous love, which is delimited from the friendly, philía (φιλíα), and the divine, agápē (αγάπη). It corresponds to the Roman equivalent Amor, also called Cupido (Latin). In the Theogony of Hesiod Eros is introduced to Greek mythology as the most beautiful of the immortals. As one of the first five deities, Eros emerges immediately after the chaos and acts as a universal primordial force in the development of the cosmos in order to bring forth what is new and to keep the existing together. Although he looks like a boy, he is older than Kronos and has unlimited power over gods and humans.

In the myths of the Greeks Eros appears mostly as a child. Innocent and mischievous he shoots his golden and leaden arrows at gods and humans. Neither gods, nor humans have a chance to fight back against the missiles of Eros. Apparently Eros was so successful with his golden (happy love) and leaden (unfortunate love) arrowheads that later he ventured not only to humans, but eventually even to gods.

He is called Cupid by the Romans and is no longer a child, but a young man who falls in love with himself. Today, Eros is the namesake of everything we call erotic.

Loves

Erotes - Cupidines

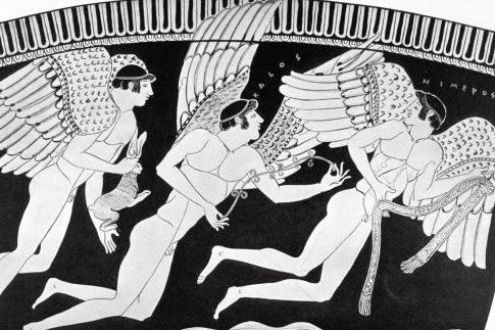

The Erotes were the winged divine forces of adoration, a multiplication of the god Eros. Hesiod portrays a couple, Eros (Love) and Himeros (Desire), while later scholars include a third, Pothos (Passion).

In later craftsmanship, particularly mosaic, they were depicted as putti (winged newborn children).

Harmony, Concord

Harmonia - Concordia

Harmonia is the goddess of concord. Her parents are the Ares and the Aphrodite.

As the daughter of the goddess Aphrodite and the god of war Ares, Harmonia is the personification of the balance of opposites. She stands for symmetry, proportion and harmony.

Her siblings are Phobos (“fear”) and Deimos (“horror”).

Harmonia and her husband Cadmus founded the dynasty of Thebes with their six children: the Polydoros, the Ino, the Autonoe, the Semele, the Illyrios and the Agaue.

Ironically, the goddess of harmony had to lead a very unhappy life. She and Cadmus left Thebes and came to Illyria after a long arduous life, where they were turned into serpents. Harmonia corresponds to the Concordia in Roman mythology.

Youth

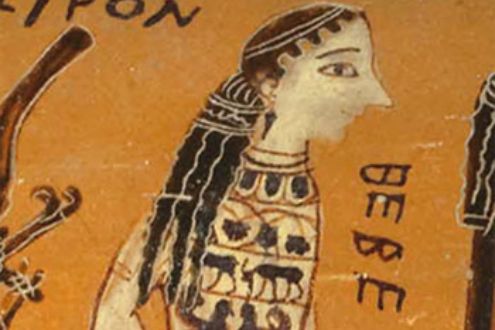

Hebe - Ἡβη - Juventas

Hebe (Roman Juventas) was the daughter of Zeus and Hera, the Greek goddess of eternal youth. She had the power to restore people to their youth. In the Olymp, Hebe worked as a cupbearer of the gods, but after she dropped while serving a drink, she was replaced by the Trojan prince Ganymede.

Hebe is the Virgin in that Goddess Triad. The three Virgins (Hebe, Hera and Hecate) also symbolize heaven, earth and underworld as well as spring, summer and autumn/winter.

Her name can be translated as “youthful flowering” as well as “youthful lust for life”. As a virgin manifestation of the goddess Hebe is said to resemble the Hurrian Hebat, the Mesopotamian Heveh or Hawwa or the Persian Hvov, as well as being a variant of the biblical Eve.

In Roman mythology Hebe finds its equivalent in the Juventas. Often it will also be similar to the Germanic Idun. Hebe is not only the epitome of youth, but she can also give even immortality.

Guardian of the golden apples

Heroes such as Heracles could become immortal gods by marrying Hebe and live in Hebe’s Garden of Paradise, where they were allowed to eat from the apples of the sacred tree. As a virgin, Hera guarded the tree full of golden apples that give eternal youth, immortality, beauty, wisdom, and royalty to the dignity of God. This was given to the Hera at their wedding of Gaia.

Bridal-Hymn

Hymenaios - Hymen

Hymenaeus (ancient Greek Ὑμέναιος, Latin Hymenaeus), in short Hymen, was in Greek mythology the god of the wedding. His name originated as a personification of the traditional marriage in the Epithalamiums song or acclamation Hymen o Hymenai, Hymen. The hymn and hymen are named after this god.

Hymenaeus is usually portrayed as a winged, beautiful youth wearing a wedding torch, a saffron veil and a wreath of flowers, especially roses, or marjoram.

Also, he is portrayed as a delicate youth of almost feminine beauty with a bride’s torch and a wreath in his hand.

He appears as a demon next to Aphrodite.

Portion of Time, Season

Horae - Ὧραι - Hora

Hora, plural Horae

Greek goddesses of order and seasons

The Horae are beautiful, benevolent goddesses who stand for order and seasons, or – if their name is translated literally – for hours.

Mothers of all things

The Horae are beautiful, benevolent goddesses who stand for order and seasons, or – if their name is translated literally – for hours.

The daughters of Themis and Zeus are sisters of the moires and a group of goddesses, which occur in the legend in varying numbers and with different emphases: Sometimes in pairs as flowering and fruiting goddesses: Thallo, the goddess of flowering or Spring and Karpo, the goddess of fruits and autumn respectively. Later, Auxo, the goddess of summer, joined them.

Order, time and annual cycle

Whether they represent the seasons or later moral forces in earlier forms, the Horae always have something to do with order – the natural or that of human society. They are responsible for the time and cycle of the year, for the cycles of plant growth and for the weather conditions in the different seasons.

They were worshiped as the mothers of all things, following each other in the fixed order day and night, the seasons, so that the months and years are filled. They make sure that time passes and so they bring the fruits of their work to people. This gives the living beings on earth security, the listeners and their order can be trusted.

It is also understandable that people put their systems of order and law under their protection.

Introduction to sexual mysteries

As nymphs of Aphrodite, however, the Horae have quite different responsibilities: they are the midwives of the deities and performed the hour dances. These represent the zodiac circulation.

This timekeeping system invented by these ancient priestesses is still called horology today. Inspired by the Horae, the Horae priestesses also introduced men to the sexual mysteries. A sacred act that relativizes the word “whores” derived from them. The word Horai should come from “I encourage” or “I keep”.

Most of the Horae are in the dance concept, their heads decorate crowns, which are to consist of palm leaves. In depictions, they are mostly surrounded by flowers, lush vegetation, and other fertility symbols.

The Hores were benevolent deities, beneficent and well-disposed towards men, offering them delights and serving them as guardians of their works. As their task was to make time roll on, they made sure that people gathered the fruits of their toil at the right moment. The Hores had their appointed occupations on Mount Olympus. In particular, it was their duty to guard the gates of Heaven, which they opened or closed by removing or replacing a thick cloud. Another of their basic duties was to serve the goddess Hera: to unhitch her celestial steeds from her chariot, tether them to their rack and look after the goddess’ chariot.

They usually sat near Zeus, with the other gods, where they sang and played the flute. They were closely associated with Aphrodite, the goddess of beauty and Love. It was they who welcomed Aphrodite when, after her birth, she came ashore on the coast of Cyprus, and who decked her in everlasting garments. They put a golden crown on her head, passed bronze and golden flowers, though her pierced ears, adorned her with precious necklaces and, thus resplendent, conducted her to the Immortals. Finally, the Hores escorted Persephone, every time she came up to the world of men.

The Hores were always obliging, and carried out the orders of the gods most faithfully. It was they who, along with Athena, the Graces and Peitho adorned Pandora, the gift Zeus sent down to earth to man’s perdition as a divine punishment. They were also assigned, at the behest of the gods, to nurture Aristaeus, the son of Cyllene, touching his lips with nectar and ambrosia to make him, like his father, immortal. They swaddled the infant Hermes at his birth, and crowned the new-born Dionysus with ivy.

The Hores, said to be born of the union of Zeus and Themis, were three inseparable sisters, called Dike, Eirene and Eunomia: Justice, Peace and Good Order. These were divinities who gave wise advice on social and political life and bestowed wealth; they also tried to remove the arrogance acquired by human beings who have everything.

They are presented as having two different aspects: on the one side, they are descended from the deities of vegetation, who were associated with the annual circle of nature. They cause time to roll on, and generate the chain of birth, death and rebirth in an incessant cycle, the circle of life itself. The worship of the deities of vegetation dates from the depths of antiquity. The fact that the Hores belonged to this group of divinities is borne out by their close relationship with such gods as Artemis, Aphrodite, Persephone, Dionysus, Hera and most of all with the Graces, with whom they shared many common characteristics. The Graces were regarded as goddesses of vegetation and fertility and, apart from the fact that like the Hores they were daughters of Zeus, they were also honored in similar fashion. The second aspect of the Hores included a social dimension: they watch over the works of the mortals and give them the wealth they deserve. The Hores assume this task only so long as they are respected., when people are fair in their dealings and faithful in their observance of the laws. Finally, if Dike, Eirene and Eunomia are highly esteemed and occupy the position they deserve in a human community, then they bring prosperity and political stability.

The Hores were also related to the Fates, with whom they shared a common parentage. The Fates, however, are more connected with the destiny of individuals, while the Hores are associated with entire societies or cities, as guardians of political and social order. The fact that Themis had given birth to both sets of divinities reflects their relationship to the divine principle of order and normality symbolised by this goddess.

The role of the Hores gradually changed. This must have occurred at a later date, probably during the Hellenistic period, when little by little the Hores came to represent only the seasons of the year, each having a specific competence. Their number varied over time as well: at first three, they later became four and eventually twelve, the number of subdivisions in a day, thus, acquiring the meaning now associated with their name: that is hours. By this time their father was said to be Cronus (Time), and their names reflected their competence: Dawn, Sunrise, Noon, Sunset, etc.

Good Health

Hygieia - Ὑγιεία - Salus

Greek goddess of health

Hygieia has been since the 7th century B.C. worshiped in ancient Greece as a goddess of mental and physical health. Hygieia had her own temples and sanctuaries. Her priestesses worked with herbs and healing stones, baths in healing springs, energizing massages and healing sessions.

She is the daughter of the Epione (Soothing Goddess) and the Greek god-physician Asclepius (Aesculap).

In the Temple of Asklepia, gynecology was practiced under the sign of Hygieia. Women sought out the priestesses of this goddess especially for childlessness and pregnancy problems. Women decorated the statues of the goddesses with their own hair and clothes.

Hygiene and preventive health

The Greek goddess of health is still very present in our lives today. As the epitome of health, we owe her the term hygiene – which also shows her essential orientation.

While her father Asklepios has been more explicitly associated with healing, Hygieia is much less for drugs or other agents for illness, but much more for the protection of good health and preventive health maintenance, which is supposed to effect hygiene.

Nevertheless, she is also considered the protector of pharmacists. The symbol of pharmacies with a snake drinking from a bowl is also due to this goddess and is not falsely asserted as her father’s Asclepius bar. Because it was she who fed snakes with (mother) milk.

Hygieia is usually portrayed with a cornucopia full of fruits or her sacred animal, the serpent, which reaches out of a bowl of water or milk.

The shell, the cauldron (as a symbol of the uterus) and the nourishing element (the snake drinks from it) are added to Hygieia.

Her name is immediately invoked at the beginning of the oath of Hippocrates: “I swear by Apollon the doctor and by Asclepius, Hygieia and Panakeia and by invoking all the gods and goddesses.”

Her other siblings are Iaso (the goddess of recovery), Aegle (glitter), and the brothers Euamerion (happy day), Machaon and Podalirius (who, as great doctors and healers on the Greek side in the Battle of Troy their fame and Telesphoros (the leader).

Roman name

Hygieia was also called Agathe Theos, known in Rome as Bona Dea (“Good Goddess”). Their Roman counterpart is Salus.

The special day of honor, of the Hygieia is February 26th. This is the time of the “new water”, which is bubbling back under the ice and in many small streams after the snow melt over the meadows. This was considered a symbol of the new life force in the early spring. On that day, people in ancient Rome went to healing springs to bathe and drink the water.

Fates

Moirae - Μοῖραι - Fatae

Moires are the fate goddesses in Greek mythology. In Greek mythology, there are the three moires also called the Moirai. The singular of Moiren or Moirai is Moira. The Moirae correspond to the Fatae (or Fatum, Fata, Parcae) in Roman mythology. And even in Germanic mythology there are the goddesses of fate, who also determine the fate of men. These are then in particular the Norns. So Norns, Moiren and Fatae are similar.

The Moires symbolize the inevitable skill. The Moires are available in triple form. There is a Klotho. That’s the one who has the spindle. She spins the thread of life. There is Lachesis, the messenger of the scroll. It measures all the contingencies of existence. And last but not least, there is Atropos, the inevitable, the inexorable. Atropos has a pair of scissors and cuts through the thread of life, while she cuts him with her laugh.

The Moires are the children of the goddess of the night, Nyx. And there are other traditions according to which the Moires are the daughters of Zeus and Themis. The Moires sometimes appear alone, sometimes in twos, sometimes in threes and sometimes in fours. The Moires can also be seen as past, present and future. You can also look at them as the three aspects of life. The three wise women. There is just the virgin, the mother, the old woman.

The maiden spins the thread of fate, life begins. The mother measures the thread and the old woman cuts through the thread of life. Sometimes it is said that the three also sing and sometimes they connect with each other. In this sense, the three Moires stand for the fate of man and everything else. Everything has a beginning. Everything has a life span. And everything will eventually come to an end.

The Moires, though determining the fate of all life, guarding life are most associated with birth and death.

Originally, they were supposed to have supervised the birth of the people and immediately afterwards assigned their lives to them. According to later records, they appear three nights after the birth of a child to determine the course of his life.

They are therefore especially respected and honored because they distribute fairly. Faith in women of destiny is associated in many cultures with different customs at birth.

Muse, Muses

Muses - Μουσαι - Musa

Goddesses of the arts

Hesio set her number to nine. These were Klio, Melpomene, Terpsichore, Thalia, Euterpe, Erato, Urania, Polyhymnia, Calliope. There are names for a three more, Aodete, Melete and Mneme – presumably in an attempt to adjust their number to the divine number twelve.

The muses were nymphs; According to some sources, their sacred mountain was the Helicon in Boeotia, and after others they were the nymphs of the springs of Mt. Parnassos. Others claim that they were born at the foot of Mount Olympus.

Here are their names and responsibilities:

Erato: The muse of the hymn, the song of love. She is often depicted with wreathed hair playing on a lyre.

Euterpe: The muse of the music is represented standing, playing on a flute.

Calliope: The Muse of the heroic epic, sitting, depicted with stylus and blackboard. Referred to by some sources as the leader of the muses.

Clio: The muse of the story is often depicted sitting with a laurel wreath in her hair, a half-open scroll in her hand.

Melpomene: The Muse of Tragedy. She is portrayed seriously and dignified. She often holds an actor’s mask in one hand and a manuscript in the form of a scroll in the other.

Polyhymnia: the muse of storytelling and song, sometimes pantomime. She is also referred to as the inventor of the myth and presented in a brooding pose.

Terpsichore: The muse of dance is often depicted dancing, with a wreath in her hair.

Thalia: The Muse of Comedy. She holds a shepherd’s staff in one hand, an actor’s mask in the other hand.

Urania: The Muse of Astronomy. It is sometimes depicted sitting and with one hand pointing upwards.

Victory

Nike - Νίκη - Victoria

Greek goddess who embodies the victory, the personification of earthly glory

The goddess Nike is mentioned by Hesiod. She is the daughter of Styx and the Titan Pallas. She has a number of siblings – Bia (violence), Zelos (emulation); Kratos (power), Vis (power), Invidia (envy, resentment, jealousy), Potestas (power, authority) – all of these siblings seem to be involved in some way in making a victory.

Intervention in the fight against the Titans

Together with her mother Styx and her siblings, she supports Zeus in his fight against the Titans.

In Greek mythology, long before the birth of humanity, there was an eleven-year war between the two deities called the Titanomachy. The Titans of Mount Othrys, led by Kronos fought against the children of Kronos and Rheia under the leadership of Zeus. The party of Zeus won this fight, especially with the help of Styx and Nike. With this, Nike won the right to settle on Olympus. As the goddess of victory, she also actively intervenes in the fighting and leaves the battlefield with bloodstained robes.

The desire for success

But not only in the fight, but also in the peaceful (for example, in the sporting and artistic) competition Nike is asked for the victory.

Victory wreath and palm leaf

Nike is usually portrayed as a slender, elegant woman whose gauzy robe flutters in the wind. She is mostly winged and holds a wreath of victory in her hand.

The brave “fly” Nike as a victory

However, the most important attribute of the hurrying goddess Nike is the wings. Often Zeus or Athena carries the image of Nike to show that those deities can only achieve victory through the power of Nike. Sometimes Nike is also mentioned as a form of Athena.

From antique vase paintings to modern sports shoes

Nike is a popular figure that has been featured frequently in many eras. Her portrait appears on antique vase paintings as well as the stylized depiction on sports shoes of modern times.

Nike can be found in the relief sculpture, in the Toreutik as well as an architectural element. The sculptor Archermos from Chios created the first winged Nike with four sickle wings, diadem in the hair, long robe and winged shoes in the 6th century BC. During the 5th century BC. Nike eventually becomes the official victory monument.

Probably the most well-known surviving example is “Nike of Samothrace”, now in the Louvre in Paris. This sculpture was found in the sanctuary of the Kabiren on the Greek island of Samothrace. It was probably created around 190 B.C. in Rhodes. Later angelic portrayals, especially in the Renaissance, were often inspired by the ancient Nike depictions.

Healer

Paeon - Παιων - Paean

Paieon is in Greek mythology, the son of Chromia and Endymion, the king of Elis.

A very old healing god whose name can be found on Linear B tablets. He heals Ares after being wounded during the Trojan War.

Paian appears as an individual god also in a fragment of Hesiod and Solon, who traces the knowledge of the medical arts back to Paian’s mediation.

Desire, Longing, Yearning

Pothos - Pothus

Pothos (Greek Πόθος “desire”) is in Greek mythology the brother of Eros.

Pothos is the personification of the longing, sadness and sweet desire. Pothos is also the brother of Eros.

Regardless of the exact family relationships, Pothos was closely linked to Eros and Himeros, the personification of the desire for love. While Eros and Himeros already appear together in Hesiod’s Theogony and appear with the birth of Aphrodite, Pothos occurs later.

Fortune, Chance

Tyche - Τύχη - Fortuna

In Hellenism her worship grew. Antioch and Alexandria worshiped Tyche as the city patron. The Roman equivalent is the goddess Fortuna.

The earliest mentions can be found in the theogony of Hesiod around 700 BC and in the Homeric hymn to Demeter from the second half of the 6th century BC. They describe her as the daughter of Oceanus. However, she is then called the daughter of Zeus Eleutherios.

Before she became a goddess of fortune, Tyche was considered the bearer of wealth. Originally she was a nautical goddess, in port cities she was considered a goddess and lucky charm of the seafaring.

Tyche embodies, however, the unpredictable aspect of happiness, it favors above all the coincidence, which decides about luck and misfortune. The only way to approach Tyche’s favor is to lead a restless, adventurous life, not to be on the safe side and challenge fate again and again.

God of medicine

Asclepius - Vejovis

One of the most interesting figures in Greek mythology is Asclepius. His name is associated with the science of medicine: indeed, he is considered to have been the first doctor.

Son of a god and a mortal woman, Asclepius was not reckoned to be among the mighty gods who lived on Olympus; instead, he was considered to be a demigod of divine origin. He was the fruit of one of Apollo’s numerous love affairs. The handsome god fell in love with a princess, the beautiful Coronis, who conceived a son. However, before giving birth to the child, the young lady yielded to the love of a stranger whose name was Ischys. She soon regretted her frivolous action, but it was too late. Apollo, who realized her deceit, in his rage asked his beloved sister, Artemis, to punish the young Coronis for her irreverence. The goddess, sending her arrows, killed her together with a number of other women; this, apparently, was the cause of a fatal epidemic which broke out in that area. Because of the disease, the corpses were placed on funeral pyres to be burned. As the dead body of the princess was being devoured by the flames, Apollo, who was watching the scene, could not bear to see his child die with her. He rushed into the flames and saved the babe, who was about to be born, snatching him from the burning pyre and carrying him to Magnesia, where he was put in the care of the Centaur Chiron. Chiron was adept in the properties of plants and he instructed Asclepius in the science of medicine. Through his miraculous cures and curative powers, Asclepius soon won immense fame. Indeed, the ill and the injured came to him in their despair from all over Greece.

Asclepius was able to cure all kinds of illnesses. The ill were restored to health thanks to the herbs he gave them, to the miraculous ointments which Asclepius prepared himself or by means of magic devices and prayers. He even cured people of madness, as it is said he did of the daughters of Proetos, when Hera afflicted them with insanity. Others, he made a walk to see the light again. Indicative of the importance of Asclepius is the numerous sanctuaries dedicated to him throughout Greece; many of these, of course, were probably founded by his priests.

Asclepius was greatly liked, and the people venerated and respected him, perhaps because he was not unapproachable and did not, like the rest of the gods, cause fear. On the contrary, his position was always near the people; offering his knowledge for their benefit. He gained fame inside and outside Greece. The God of Health made efforts to diffuse the science of medicine, to cure more and more people of their diseases, to establish special buildings (Asclepoieia) where people could go seeking therapy. In the sanctuaries of Asclepius, his priests, called Asclepiades, continued his activities. The most famous of all the sanctuaries is the Asclepeio of Epidaurus, followed by those situated in Athens, Kos – the birthplace of Hippocrates, the father of medicine – and Pergamum. When the patients arrived at the sanctuary seeking therapy, they were allowed to enter and spend the night in the temple only after much preparatory purification: baths, strict fasting and sacrifices offered up to the god.

The devotion to Asclepius was so great that people came to view him in the same light as the other gods. Asclepius, like Hercules, was eventually deified and thus gained admittance to the abode of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Asclepius, as the son of Apollo, possessed powers of divination or (as many believe) he, like Pythia, disclosed to mortals what his father had revealed to him. Be that as it may Asclepius gave his prescriptions in the form of oracles. His priests explained to the patients who spent the night in his sanctuary that the god would appear in a dream and give them advice about the medicine which could cure them. The great god of health not only cured every disease, but he also succeeded in restoring the dead to life. Thus, when the Goddess Artemis asked him to resuscitate her beloved Hippolytos, he brought him back to life. However, this miraculous power of Asclepius in the end caused his own death. Legend has it that after one such resuscitation Zeus was enraged and, blinded by his ire, struck Asclepius dead with his thunderbolt.

Others say that it was not his own personal ire that drove the king of the gods to kill Asclepius, but the rage of Hades, who felt that he was being cheated: the god and sovereign of the Underworld went to Zeus to complain that the son of Apollo was not permitting human beings to die and that as a result fewer and fewer people were entering his realm. Apollo was mortified by the loss of his son. He had saved his life once, when he was still in his mother’s womb, but this time, he was unable to act. Such was his sorrow and rage that he avenged the death of his beloved son by killing the Cyclops who had presented Zeus with the thunderbolt he always held in his hand and which he had used to cut the thread of Asclepius’ life.

The Messenger Goddess

Iris - Ἶρις - Arcus

Goddess of the Rainbow, Fertility, Colors, the Sea, Heraldry, the Sky, Truth, and Oaths

Iris was the daughter of Thaumas and Electra (one of the daughters of Oceanus). She wore a short tunic, winged golden sandals and in her hand held the caduceus. A winged goddess and, rapid as the storm-winds, she was known as the faithful and swift-footed messenger of the gods, delivering their messages to gods and men, and assigned to intervene between the gods whenever problems arose.

She was said to be the sister of the Harpies, who were also winged, airy creatures, as restless as the wind and storm, and Zephyrus was her mate.

Her basic duty was to contribute to the awarding of justice, whenever quarrels or rivalries broke out among the Olympians or whenever a god told a lie. Then Iris would have to soar up to the abode of Styga, where Heaven was supported on silver pillars and from where the sacred waters of the Styga rained down upon the earth. Here she would fill her golden cup with this water and bring it back to Olympus. If a god swore a false oath by these sacred waters, he would fall senseless to the ground, remaining unconscious and unbeaten for a long period of time; nor could he feed on nectar and ambrosia. For nine years he would remain excluded from the company of the gods and be deprived of their protection.

Iris not only carried out the missions assigned her, but she frequently acted on her own initiative. According to the Iliad, she took the wounded Aphrodite and led her away from the battle. She also entered Helen’s room and inspired her to go out and watch Paris and Menelaos, who were about to duel together. She often moves in advance of Olympian wedding ceremonies and stands by the bride, as she did during the nuptials of Thetis and Peleas and of Zeus and Hera.

Iris’ basic mission –and an extremely important one it was – was to deliver Zeus’ orders to the gods, especially to Poseidon. She could however also deliver messages for other gods, as happened in the case of Leto. The Olympian goddesses, with the exception of Hera, called upon Iris to intervene in order to help Leto deliver her children, Artemis and Apollo. Hera, as we know, persecuted Leto and did not allow the birth to take place, detaining on Mount Olympus the midwife goddess Eileithyia, who brought to women in labor the delivering pains of childbirth. As Leto’s delivery was delayed, Iris was sent in secret to Olympus to fetch Eileithyia to help the labouring woman, promising her, in accordance with the instructions given her by the Olympian goddesses, a necklace with nine beads strung on a golden thread. In other cases Iris acted as Hera’s personal servant: in the Iliad, she acted for Hera, persuading Achilles to rejoin the battle when his friend Patroclus had been killed and Hector wanted to carry off the hero’s dead body. It seems that in a later period she was assigned exclusively to Hera’s service: people imagined her seated, like a faithful dog, in front of the goddess’ throne, never leaving her, never removing her belt or sandals, always alert in case the queen of the gods should suddenly send her on a new and urgent mission.

Whenever Iris had to carry a message from a god to the world of men, she would assume the shape of a mortal. For example, she intervened in the Trojan camp in the shape of one of Priam’ s sons, and appeared to Helen in the form of her sister-in-law. Mortals, as well as the gods, experienced her good nature. Towards Achilles in particular, she was especially well-disposed. When she heard him invoke the help of the Winds because the flames of the pyre were slow in devouring the body of Patroclus, she immediately went to find them so that his wish should be satisfied. Finding them foregathered in the cave of the North Wind, Boreas, for a solemn feast, she interrupted the festivities in order to explain the reason for her visit and to transmit Achilles’ wish. Only one place of veneration dedicated to Iris is known from the ancient times: this was the island of Hecate, near Delos.

Nowadays the goddess’ name has acquired different meanings. We call ‘iris’ the colored portion of the eye, and it is also the name of a flower. Its basic meaning, however, is ‘rainbow’. Although Homer first used the word “iris” to express the physical phenomenon of its appearance in the sky, the goddess Iris has never been the personification of the rainbow, and while there are many representations of the goddess in ancient times, she is neither depicted as a rainbow nor accompanied by one.

Essentially, it is in the minds of men that the rainbow has been identified with Iris, initially with the person of the goddess and later with her robe or her path across the sky. Indeed, Iris’ identification as a messenger of the gods is based on precisely this association: the rainbow seems to link heaven and earth, sky and sea, just as Iris, as a bearer of messages, moved between the gods and men, even to the depths of the sea and down to the Underworld, hastening with the speed of the wind.

Spirits of nature

Nymphs - νύμφη

The Nymphs were young female beings of divine origin, who lived in the wild, rambling over the mountains, accompanying Artemis and playing with her. They were all very beautiful, but none could compare with Artemis. They sang and danced together with Pan in the meadows and on the mountainsides, usually near the springs. With their sweet voices they celebrated the Olympian Gods, and especially Hermes, who was Pan’s father. Homer tells us that Aphrodite and the Graces danced with them on Mount Ida, near Troy, adding that sometimes their dance was led by the god Apollo himself. The Nymphs were generally considered to be something between gods and mortals, rather than real divinities. They were not immortal, but they lived for many years and fed on ambrosia.

They were related to the great gods; Hermes, in fact, was considered to be the son of the nymph, called Maia. According to other accounts they were the daughters of different rivers, either major rivers such as Oceanus – the biggest river of them all – and Acheloos, or smaller local rivers. Every region, of course, had its rivers, which begat the Nymphs of that area: for example, the river Peneios was the father of the Nymphs of Thessaly, and the river Xanthus was the progenitor of the Nymphs of Troy. They very often gave their name to nearby towns, as was the case with the Nymph of Sparta, who was the daughter of the river Eurotas. There were also other Nymphs, known as Meliae (Ash-tree Nymphs) who were born of the drops of Uranus’ blood, which dripped onto the Earth when his son Cronus mutilated him, casting his bleeding genitals into the sea.

They were essentially freshwater spirits, living in the rivers, the springs and among the mountains which gave rise to the rivers. They always accompanied water, thus underlining its great importance to life. Without it, there can be neither vegetation nor fertility. Through their association with the life-giving power of water, therefore, the domain of the Nymphs spread to the mountains and the forests, connecting them with the vegetable world. This is the reason why they were considered to be the daughters of the Ocean or of other rivers.

The Nymphs were classified, according to their place of abode, into three types: 1) The Naiads, or Nymphs of the rivers, the springs and the fountains; 2) The Oreads, who lived on the mountains where there were springs and 3) The Dryads or Hamadryads, or Nymphs of the solitary trees and meadows, who were identified with the Meliae.

The Naiads lived in caves which were near or in the water, under the surface of the rivers. In their caves, they enjoyed the delights of love with Hermes or Selenus. The duration of their life was strictly connected with the life of the springs near which they lived: as soon as the springs dried up, the Naiads died. The same happened to the Hamadryads – whose name means “tree and women at the same time”: the pines, the fir trees and the oaks began to grow up as soon as a Nymph came into being. These trees were strong and long-lived, and the mortals were forbidden to touch them with an axe, for they were considered to be sacred: indeed, the sacred groves formed by these trees were places dedicated to the gods. When a Nymph was about to die, her tree withered first under the ground. A Nymph once grew pale when, while dancing with her peers, she saw her oak tree shaking to and fro. Filled with apprehension she stopped dancing; soon the bark of her tree was destroyed, its branches dropped and at that very moment the spirit of the Nymph passed away, making her farewell to the light of Helios. The Nypmphs were happy when it rained, because the rain nourished the trees, and they wept when the oaks lost their leaves.

There are many legends about the Naiads, telling of their amorous adventures. It is said that once upon a time Hylas, Hercules’ companion, having gone in search of water, discovered a fountain where the Nymphs used to gather and sing praises to Artemis all night long. Hylas had come near the fountain to fill his jug just as they began to gather there. One of them, Ephydatea, who lived in the fountain, raised her head and saw him. She was so dazed by his supreme beauty that she fell in love with him. Hylas, bent over the fountain, and plunged his pitcher into the waters without suspecting that he was being observed. The Nymph, wanting to seize the opportunity to kiss him, put her arms about his neck and dragged him into the depths of her watery abode. He was never seen again by his companions. They searched everywhere for him, but could not explain his disappearance.

The stories of the Nymphs’ love affairs with the shepherds who grazed their sheep by the riverbanks were also well-known. From those unions, the Nymphs gave birth to sons mortal, but wise and brave.

The stories about Apollo’s love affairs with the Nymphs (especially the tale of Daphne) were equally well-known. Apollo tenaciously laid siege to Daphne but without success. As soon as the opportunity came his way, he began to pursue her. When he was about to catch her; Daphne implored her mother Gaea to help her. Immediately the earth gaped open. Daphne suddenly disappeared and in her place a laurel tree sprang from the ground.

Another Nymph, Hocyrrhoe, who was the daughter of a river on the island of Samos, tried to flee the island on a boat, in her endeavor to escape from the god’s hands. However, her efforts were in vain, because Apollo transformed the boatman who was carrying her into a fish and his boat into a rock.

According to tradition, the Nymphs served as wet-nurses to many of the important gods or heroes, taking care of them in their early infancy and suckling them at their own breast. Zeus, first and foremost, was brought up by the Nymphs on the island of Crete, as were Hera, Persephone, Hermes, Pan and Dionysus. Aphrodite confided her son Aeneas to the Nymphs of the Trojan mountain of Ida. The Nymphs, together with the Satyrs, subsequently joined the company attending Dionysus.

The Naiads were thought to possess various powers; indeed, people believed that they could make the waters of a spring curative and this explains why mortals often offered up sacrifices in their honor. The best-known cases of Naiads with such powers were found in the Peloponnese and in Sicily; indeed, they say that Hercules used to go there, to the thermal springs of Hemera, to renew his strength. It was also believed that the Naiads had therapeutic powers, mainly because of their relationship to Apollo, as well as the gift of predicting the future. There was also a widespread belief that the Naiads could interpret the will of the superior divinities, especially Erato, the desires of Pan, and Daphne and those of Gaea. In the cave Sphragidion in Mount Cythaeron there was once an oracle of the Nymphs, while many mortals, gifted with prophetic powers, claimed that these had been bestowed upon them by the Naiads. The Naiads were also considered to be the mothers of many wise mortals, soothsayers and doctors, like Chariklo, daughter of Teireseas, Philyra, daughter of Chiron, and Coronis, the mother of Asclepius.

While the Nymphs were worshipped in many places throughout Greece, no temples were dedicated to them. The sacrifices offered in their honor took place near the springs or in caves. Ulysses and the inhabitants of Ithaca venerated them with a Hecatomb, which is a sacrifice of a hundred oxen. They often had altars in the temples of other gods. The action of the Nymphs, however, were not always beneficial to mortals, to whom they sometimes caused great harm. If, for example, someone happened to see a Nymph when she was bathing in her spring, he would lose his reason. One of their powers, in fact, was to be able to throw mortal minds into confusion, and drive people mad. Those who were overcome by ecstasy and enthusiasm, abandoned their homes and went to the mountains, where they hid in caves.

The Nymphs have survived in folklore and popular tradition: they are the familiar fairies who live in the mountains, the fairy-grottoes and the fairy-springs. It is still believed that it is dangerous to meet them: indeed, stories are still told about the “moonstruck”, like Hylas in ancient Greece. Tradition has it that only the fey and those born on a Saturday can actually see the fairies and watch them while they are dancing.

Finally, it is worth stressing once again that the Nymphs were worshipped as elements of the springs and the rivers, and of water generally. The importance of water to life and fertility is immense and, in a Mediterranean country like Greece, vital. Water is a source of life and contributes to the development and the renewal of each living organism. This explains why the concept of the Nymphs was broadened: people went as far as to think of them as spirits of vegetation, wanting in this manner to symbolize the exuberant power of nature. And just like the water which nourishes everything, the Nymphs were considered to be the wet-nurses of plants, of animals and of human beings.

God of Nature

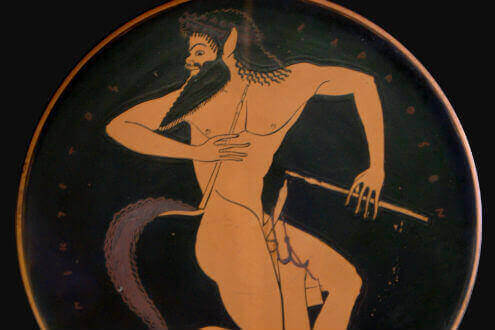

Pan - Πάν - Faunus

Pan is a strange-looking god, who is often seen in the joyous retinue of Dionysos. His grotesque appearance frightens all who come near him, and only in the company of the Satyrs is he received enthusiastically, as he too loves singing and dancing.

Pan was the son of Hermes, the messenger of the gods. While grazing the sheep of a mortal in a wonderful place in Arcadia, the winged god noticed among all the beauties of nature the loveliness of the Nymph Dryope. He fell in love with her, succeeded in seducing her and before long she gave birth to the fruit of their amours. The child she brought into the world had a repulsive appearance: his legs were the legs of a goat, his face was covered with a long, bushy beard, his ears were pointed and two horns poked through the tangle of hair on his head. Terrified at the sight of him, Dryope ran away, abandoning her son. Hermes felt compassion for the child, took him in his arms and carried him to the abode of the gods, on Mount Olympus. When the gods saw him, they all, amused by his appearance, began to laugh, and most of all the god of gaiety, Dionysos, who, to Pan’s great joy, invited him to join his retinue. And since the sight of Pan on Olympus amused “all” (in Greek “pan”) the immortals, he was thenceforth known as Pan.

Pan spent most of his time in the countryside. He rambled among the rocks, over the mountains and through the creeks, spreading far and wide the melodies of a new sort of flute which he called syrinx. According to legend, this flute was the result of Pan’s unsuccessful pursuit of the beautiful Nymph Syrinx. One day he was chasing her and had nearly caught her when she cried aloud to the river-god Ladon, to change her into a reed. Her prayer was granted and instead of the beautiful Nymph, Pan found himself clasping a slender reed. The unhappy Pan was standing disappointed by the riverbank when he heard the sound made by the breeze as it passed through the reed he was holding in his hand. He then cut more reeds of different sizes, bound them together in graduating lengths, and thus created the syrinx.

Pan was a very good musician, and with his melodies he enchanted the animals, the birds, and the Nymphs of the forest. His songs gave rhythm to the steps of every dancer. At any moment he was ready to dance and enjoy himself, either with the Nymphs or with the retinue of Dionysos. He always held in one hand the syrinx, known otherwise as the pipes of Pan, and very often, in the other, a shepherd’s crook, for Pan was the god of the shepherds. He was considered to be the protector of herdsmen, and also of those who fought and struggled justly, for they believed that with Pan’s help they would manage to put their adversaries to flight by giving them a sudden fright, called for this reason panic, that fear which coming over people makes them seek safety in flight.

Apart from Syrinx, the ugly god tried to seduce another Nymph. But in vain: the Nymph Echo, who had fascinated him with her melodic voice, was no more willing than Syrinx to receive the attentions of the goat-legged divinity. Pan, unable to win the Echo’s love, took his revenge by sending his protégés, the shepherds, to attack the unlucky Nymph. Only the Nymph Pitys agreed to stay with him, preferring him to Boreas. But Boreas, enraged, hurled her against a rock and in pity Gaea transformed her into a pine. Thus, Pan’s desire for love remained unfulfilled once again.

Spirits of nature

Satyrs and Maenads

During his wanderings Dionysus was followed by a large, boisterous band which gathered round the god of amusement and made a great noise as with their shouting and singing. Plenty of wine was poured and fun reached a climax. The happy, carefree company traveled from country to country to teach people the art of vine-cultivation and wine production.

Their travels were a non-stop round of a crazy public feast. Their over-excitement and joy was passed on very easily to those they happened to find on their way, while those who tried to resist, underestimating their powers, found themselves in real trouble. People from India, for example regretted having attacked them since after a series of battles that lasted three years, they were forced to accept Dionysus and his escorts. One could see strange-looking people among those who followed the god; the Mainades, the Satyrs, the Silenis and most of the time, the god Pan.

The Mainades (Maenads) represented the female element of the company and they held the “thyrsos” as the god did. The Thyrsos was a reed covered with winding ivy or vine leaves. Sometimes they held snakes or other animals. Their clothes were light so that they could dance easily. When they were possessed by the spirit of the god they went into an endless frenzied dance. During that time they looked as if their spirits came out of their bodies because their actions were directed by intoxication into an ecstasy. Sometimes their dance became wild and formidable.

When they were possessed by rage – hence the name Mainades – they did not know what they were doing. Overexcitement led them to irrational actions. For example Penthea’s mother cut her very own son into pieces with the help of the rest of the Mainades.

The Mainades in Thrace acted in a similar way cutting the Orpheus’ body into pieces when they found out that he started to hate women after being disappointed in his love-affair. The Satyrs and the Silenis danced and had fun either alone or together with the Mainades. They were strange-looking figures – a combination of both human and animal features. They were bald with pointed ears and had tails. The Satyrs had the legs and tails of a goat while the Silenis had the legs and tails of a horse.

Ancient Greeks represented them mostly as slender young men. The only signs that betrayed them as Dionysus companions’ were the pointed ears and the tail, which of course gave them the charming element of their character. On the other hand, there were times when they were represented, raging with wild, beastly features. They always gathered round Dionysus during the feasts, dancing endlessly to the sound of musical instruments or playing the pipe and the guitar themselves. There were also faithful servants who very willingly came running to help Dionysus whenever he called during the grape-harvest and the wine pressing season. After all, this was one more job which was fun for the god’s cheerful companions. Moreover, they assisted the god when he tried to bring Hephaestus back to Olympus. All of them treated the divine blacksmith to plenty of wine and when he was drunk they led him on the backs of their donkeys to the Gods’ Residence. Donkeys were their favorite animals because they had frightened the Giants with their braying while they were at war with the Olympian Gods. As Dionysus faithful assistants they could hardly resist the god’s call. As a result the Satyrs, the Silenis and their animals were the strangest army that the gods had ever happened to have, though surely very valuable.

Lively and playful the Satyrs and Silenis brought joy and entertained the people. However, sometimes, their tricks had no limits and ended in annoying results. They teased everyone. All of a sudden, they would start to chase the Mainades and they had fun by looking at them as they were running to get away. They teased any hero they happen to find in their way. Once Perseus met them on his way back from the Mermaids. However when he showed them the Medusa’s head they were frightened and fled. Deep down they were cowardly and not so bold. No matter how much they annoyed Hercules they never dared to confront him. They always ran to be rescued every time he took notice of them. The son of Zeus was a good friend of Dionysus but Dionysus’ lively companions went in fear of him. One day they found the hero sleeping and tried to snatch his weapons. Hercules, after a quick peep, started chasing them. They even fought with the gods. Once three Silenis had a quarrel with Iris. The goddess was furious because the Silenis wanted to snatch the sacrificial animal she had been offered, from her altar.

Their disrespect was so far beyond acceptable limits that once they even tried to rape Hera, the wife of the Father of Gods (Zeus). However, they left her and ran away when they espied Hercules coming towards them. The goat-legged companions of Dionysus were very cunning, but not able to control themselves.

There were times they acted rudely, annoying gods and people, and other times when they danced and played music charmingly.

One of the Satyrs named Marcyas was famous for his great ability to play the flute. His arrogance made him challenge the god of music Apollo to a music contest. They both played filling nature with wonderful tunes. Medas, one of the two judges, suggested that Marcyas should be the winner. Apollo got angry and punished him for his disrespect turning his ears into the ears of a donkey. Marcyas’ end was even more tragic as the god skinned him alive.

Marcyas’ elder brother, old Selenos, also stood out in this anonymous and noisy band. Apollo was his father, whereas others believed it was Pan. His children, Centaurus, Pholos and Staphylus, were also famous. Staphylus was known as the shepherd of Oineas and he was also the one, the Nymphs entrusted to educate young Dionysus. Later when the god started his distant travels he was followed by his faithful teacher. Everyone, in Dionysus’ company, loved and respected him. They admired his wisdom and his immense knowledge. They couldn’t help listening to him singing his stories that dated back to ancient times. It was surely Dionysus who loved him best. Therefore, he agreed to reward Medas with anything he would ask for, since he found and brought back his old teacher when he had been lost.

snatchers

HARPIES - ἅρπυια

The Harpies were legendary flying monsters with a terrifying look. Their name implies “snatchers” because they had wings which helped them to follow the puffs of the wind and snatch everything, objects or men. The word Harpies came to be synonymous with the words storm-winds and hurricanes. If someone at sea happened to disappear, as in the case of Odysseus, the Harpies were responsible for it. It was generally believed that they snatched living souls to bring them down to Hades supplying in this way the lower world with new residents.

They imagined them as women with beautiful hair and feathers on their shoulders, but with crooked claws to snatch their prey. In still later times they had the body, legs and claws of a bird but human hands and head. Their origins are quite obscure. Some believe that they are the daughters of Poseidon or Typhoeas, others that they are Thaumanta and Electra’s (one of the daughters of Oceanus). There is also confusion as to their number. Some believe that they were two. Aello (Stormwind) and Okypete (Swiftwind) and that their sister was Iris, Zeus’ messenger. Later we meet one more, Kelaino (Dark). Homer, on the other hand mentions only one Podarge (Fleet-foot). Podarge, after a love-affair with Zephyrus, gave birth to the two famous immortal steeds Xanthos and Balios (Chestnut and Dapple). Both of these steeds belonged to Achilles and could speak like humans. Podarge was also considered to be the mother of two other famous and fast steeds Flogeus and Arpagus both of which were Dioskouros’ horses.

The Harpies were particularly known mostly from Phineus’ tale who had acquired navigating skills thanks to Apollo. However he abused the god’s favor betraying the secret decisions of Zeus to all, which was considered to be a mighty offence. Therefore raging Zeus punished him. He blinded him, condemned him to eternal old age and incapability of quenching his hunger. So every time he sat at the table the winged Harpies from above dived and snatched his food or left him some so that he could keep himself alive and be tortured. Moreover, they befouled his food with some disgusting odor, which was unbearable and therefore kept people at a distance. In this miserable situation, old and completely exhausted by hunger, the Argonauts found him in the Bosporos. They were looking for him because they wanted to ask for navigational advice. Phineus promised to help them, but asked, as a reward for them, to deliver him to the winged Harpies.

He knew, thanks to his prophetic abilities, that two specific members of the “Argo” crew were destined to chase the Harpies away. Those were the so-called Boreades (sons of Boreas) with the names of Zetes and Calais. Moreover, both young men were the brothers of the foreteller’s wife. He asked them to save him and gave his promise that they would not run any kind of danger from monsters at sea. The Argonauts agreed and when the Harpies appeared the Boreades (wind) rose into the air, puffing and howling. They chased them over the sea as far as the Plotes islands or Strophades (turning), as they came to be named, because Iris and Hermes bade them go back and swore that Phineus should have no more trouble from the Harpies. The Harpies hid in a cave in Crete. Therefore Crete, Strofades, Thrace or Skythia are thought to be their possible hide-a-ways.

We also meet the Harpies in the tale of the daughters of King Pandareos. These girls, left orphans, were favored of the goddess Aphrodite, who nurtured and taught them. As they grew up other goddesses such as Hera and Artemis came to endow them each with special qualities. When they reached maturity Aphrodite went to ask Zeus to provide husbands for them and happy marriage. Then, being left alone by their protectress Aphrodite they were snatched away by the Harpies and given as servants to the Erinyes.

As we have already said the Harpies were snatching spirits that symbolized the sudden blow of the wind and hurricane that destroy everything in their way. They were goddesses of the wind and death spirits, as well, who snatched souls. That’s why in the tales we meet them connected with figures having to do with action, perpetual movement and speed while they themselves had famous steeds as offsprings.